Something was wrong here. Something was very wrong. Talisman spent the whole morning loading the cart with stones – most of which were almost too heavy for her to lift – and hauling them to the orchard.

Something was wrong here. Something was very wrong. Talisman spent the whole morning loading the cart with stones – most of which were almost too heavy for her to lift – and hauling them to the orchard.

By the time she was done, she was near collapsing, but at a shouted order she pulled herself to her feet again. But why? Why was this happening to her? I didn’t know – her mind was as fogged as Alys Malherbe’s had been, when she had been hatching her secret plan.

By the time she was done, she was near collapsing, but at a shouted order she pulled herself to her feet again. But why? Why was this happening to her? I didn’t know – her mind was as fogged as Alys Malherbe’s had been, when she had been hatching her secret plan.

Her next task was to carry great heavy bundles of wet washing outside and put them up on the long lines that were out there.

Her next task was to carry great heavy bundles of wet washing outside and put them up on the long lines that were out there.

All I could pick up about her was that she was desperately unhappy or worried about something; and she was angry. Underneath everything, she was like a little smouldering volcano of rage. She was younger than me as well – thirteen, going on fourteen.

All I could pick up about her was that she was desperately unhappy or worried about something; and she was angry. Underneath everything, she was like a little smouldering volcano of rage. She was younger than me as well – thirteen, going on fourteen.

Then the cook called Talisman into the kitchen – with the same scornful tone. As though Talisman Mallerby was a name to be ashamed of owning. Doing the dishes was the next task – and at least that got her hands and arms clean again. But it took ages. And everyone in that kitchen seemed to despise her so. Why were the servants treating Talisman Mallerby like the dirt beneath their feet? It made no sense at all.

Then the cook called Talisman into the kitchen – with the same scornful tone. As though Talisman Mallerby was a name to be ashamed of owning. Doing the dishes was the next task – and at least that got her hands and arms clean again. But it took ages. And everyone in that kitchen seemed to despise her so. Why were the servants treating Talisman Mallerby like the dirt beneath their feet? It made no sense at all.

Talisman was near to passing out when she was finally given something to eat: some slightly stale bread and cheese. And I caught a sudden, vivid, memory from her of how things used to be.

Talisman was near to passing out when she was finally given something to eat: some slightly stale bread and cheese. And I caught a sudden, vivid, memory from her of how things used to be.

She was remembering the dining room, the damask tablecloth spread and waiting for the places to be laid and the meal to be served. She was remembering food she didn’t have to help prepare and meals she didn’t have to clean up after. And all the time her anger boiled and bubbled away inside her.

She was remembering the dining room, the damask tablecloth spread and waiting for the places to be laid and the meal to be served. She was remembering food she didn’t have to help prepare and meals she didn’t have to clean up after. And all the time her anger boiled and bubbled away inside her.

Here she was, practically reduced to begging for her meals. As soon as she had eaten, she was sent outside to go and fetch vegetables from the gardener. She came back carrying a pair of heavy baskets filled with potatoes and onions. And I had a bad feeling that I knew just who was going to have to prepare them. I wasn’t wrong either.

Here she was, practically reduced to begging for her meals. As soon as she had eaten, she was sent outside to go and fetch vegetables from the gardener. She came back carrying a pair of heavy baskets filled with potatoes and onions. And I had a bad feeling that I knew just who was going to have to prepare them. I wasn’t wrong either.

Eventually the day drew to a close. Every muscle and bone in Talisman’s body ached with weariness, yet she didn’t seem keen to go to bed. When I saw where she slept, I worked out why. I’d never seen a box bed before: it’s a bed built into a cupboard basically, with storage above and below, and doors that you can shut. And, in this case, lock. And that’s what happened to Talisman every night; the doors of the cupboard were shut and locked on her.

“And that’s no more than she deserves,” the cook said, as the door slammed shut on Talisman.

Eventually the day drew to a close. Every muscle and bone in Talisman’s body ached with weariness, yet she didn’t seem keen to go to bed. When I saw where she slept, I worked out why. I’d never seen a box bed before: it’s a bed built into a cupboard basically, with storage above and below, and doors that you can shut. And, in this case, lock. And that’s what happened to Talisman every night; the doors of the cupboard were shut and locked on her.

“And that’s no more than she deserves,” the cook said, as the door slammed shut on Talisman.

And that first day set the tone for the following ones. If Talisman didn’t work hard enough to satisfy the cook (and she frequently failed to satisfy her) then shouting and scolding was her lot.

And that first day set the tone for the following ones. If Talisman didn’t work hard enough to satisfy the cook (and she frequently failed to satisfy her) then shouting and scolding was her lot.

Too often, Talisman answered back, or was insolent in another way.

Too often, Talisman answered back, or was insolent in another way.

When this happened, she would get her ears boxed as often as not. She didn’t seem to learn though – meekness and humility seemed to be alien concepts to her. In her place, I would have kept my head well down. None of the servants seemed to have any affection for her, and I had to admit that she was a bit of a madam.

When this happened, she would get her ears boxed as often as not. She didn’t seem to learn though – meekness and humility seemed to be alien concepts to her. In her place, I would have kept my head well down. None of the servants seemed to have any affection for her, and I had to admit that she was a bit of a madam.

But even though she was a bit full of herself, Talisman was still having an awful life.

But even though she was a bit full of herself, Talisman was still having an awful life.Through the fog of her thoughts, I was picking up some clues about her, but it was like catching fragments of a film. India. She had been out in India and come here to Ship House with her father. But there was a lot about her time in India that she was keeping deliberately hidden: buried fathoms deep. Something that had happened – or that she had done – out there was scaring her.

And I didn’t know where her father was either. That was something else she wouldn’t look at or think about. That frightened her too.

Sometimes though, Talisman just seemed overwhelmed by everything. And again, I wasn’t surprised. This was an awful life that she – that we – were leading. But she seemed to accept, in one corner of herself, that the servants could treat her like this. Yet she hated it, furiously and fiercely resented it – but did not go and seek help as Lissa Malherbe had done. Why not?

Sometimes though, Talisman just seemed overwhelmed by everything. And again, I wasn’t surprised. This was an awful life that she – that we – were leading. But she seemed to accept, in one corner of herself, that the servants could treat her like this. Yet she hated it, furiously and fiercely resented it – but did not go and seek help as Lissa Malherbe had done. Why not?

Talisman seldom saw the outside of the house, unless she was fetching vegetables or hanging out washing, but one day she was sent to the front of the house to fetch some flowers from the gardener. I looked with interest, to see how the house had changed since I had last seen it. It was darker in colour, and seemed much more oppressive than it had in Alys’s time. And the guerdon was here somewhere – I was sure of that. Mostly because of how everyone was behaving: the petty cruelty and unkindness towards Talisman could only have one explanation.

Talisman seldom saw the outside of the house, unless she was fetching vegetables or hanging out washing, but one day she was sent to the front of the house to fetch some flowers from the gardener. I looked with interest, to see how the house had changed since I had last seen it. It was darker in colour, and seemed much more oppressive than it had in Alys’s time. And the guerdon was here somewhere – I was sure of that. Mostly because of how everyone was behaving: the petty cruelty and unkindness towards Talisman could only have one explanation.

The cook called her upstairs next – she seemed to be acting as housekeeper as well in the absence of most of the other upper servants.

The cook called her upstairs next – she seemed to be acting as housekeeper as well in the absence of most of the other upper servants.“Your cousin will be coming home soon - the business in London is nearly completed now – and this will be her room. I want this floor scrubbed clean. And just remember: it’s only thanks to your cousin’s generosity that you have a home here at all.”

Some generosity, I thought. Some home this was too.

Talisman sighed and went to get a bucket, scrubbing brush and water. What shocked me was the depth of her hatred for her cousin.

Talisman sighed and went to get a bucket, scrubbing brush and water. What shocked me was the depth of her hatred for her cousin.

When she had finished scrubbing the floor, she did something totally forbidden and sneaked into the bedroom that had once been hers. And her desire for revenge on her cousin, and her cousin’s father, was so strong I could almost taste it.

When she had finished scrubbing the floor, she did something totally forbidden and sneaked into the bedroom that had once been hers. And her desire for revenge on her cousin, and her cousin’s father, was so strong I could almost taste it.

The servants had been told to take a holiday before the family arrived, and they were planning to go out for the day by train. But not Talisman. She was dragged down into the cellars, which I noticed were now bigger and more extensive.

The servants had been told to take a holiday before the family arrived, and they were planning to go out for the day by train. But not Talisman. She was dragged down into the cellars, which I noticed were now bigger and more extensive.

“We’ve got just the place for you.” And the cook pushed hard at a section of the wall, which swung open.

“We’ve got just the place for you.” And the cook pushed hard at a section of the wall, which swung open.“Normally this is where we store the valuable and precious things – but just this once, we’ll put the rubbish in here instead.”

It was a proper strong-room, designed to be secure against even the most determined burglar.

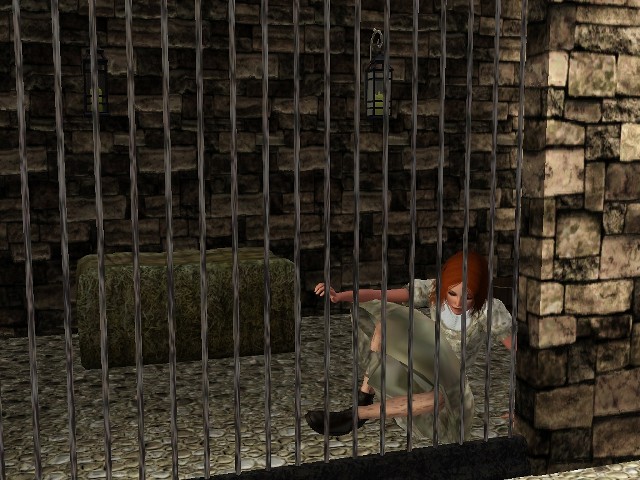

There was an old bale of straw (used for packing up wine bottles once), some bread and water, and a bucket in the corner. And a couple of candles, burning in holders. But they didn’t look like they’d last all day.

There was an old bale of straw (used for packing up wine bottles once), some bread and water, and a bucket in the corner. And a couple of candles, burning in holders. But they didn’t look like they’d last all day.

The room was locked, and the secret door swung shut on Talisman. She was left alone in the all-too-secure strong room. And I got the feeling that whatever she was afraid of was getting nearer. And it was all to do with ‘the business in London.’ Her father was there!

The room was locked, and the secret door swung shut on Talisman. She was left alone in the all-too-secure strong room. And I got the feeling that whatever she was afraid of was getting nearer. And it was all to do with ‘the business in London.’ Her father was there!Suddenly, I knew a little more. Her father was there - and these mysterious cousins. But they shouldn’t have been there! That feeling surged so strongly through her that I was almost reeling from it. They should have been – where? Talisman clamped down so firmly on the end of that thought that I had no idea what it would have been.

Talisman was left there all that day and all night too. She finally fell asleep on the floor – the straw was damp and smelly from being in the cellar for so long. The candles had burnt out, and she blinked at the light when they came to let her out.

Talisman was left there all that day and all night too. She finally fell asleep on the floor – the straw was damp and smelly from being in the cellar for so long. The candles had burnt out, and she blinked at the light when they came to let her out.

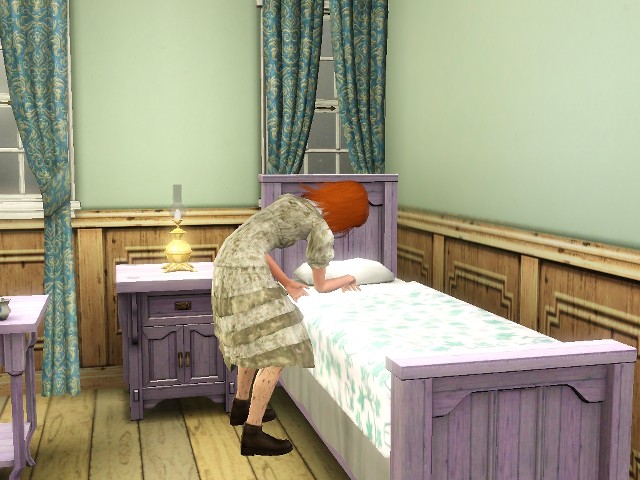

The floor had been scrubbed to the cook’s satisfaction, the furniture had been moved back in, and Talisman had been sent to make up the bed.

The floor had been scrubbed to the cook’s satisfaction, the furniture had been moved back in, and Talisman had been sent to make up the bed.“And be sure you do it properly. Or I’ll have something to say to you.”

Talisman did not dare do anything other than a good job, but inside she was seething with fury. I caught glimpses of what she would like to do to this cousin, and they weren’t pretty glimpses.

“We need to get you cleaned and tidied up. You look a disgrace like this.”

“We need to get you cleaned and tidied up. You look a disgrace like this.” And the dress she had been wearing – which had once been a pretty and elaborate affair – was taken off her, and she was given new clothes to wear.

“The family will be here next week. And from now on, your role is that of scullery maid. You don’t leave this kitchen. Your place is on this side of the door. And whilst we’re at it, let’s tidy your hair up a bit, shall we?”

“The family will be here next week. And from now on, your role is that of scullery maid. You don’t leave this kitchen. Your place is on this side of the door. And whilst we’re at it, let’s tidy your hair up a bit, shall we?”

And the cook and one of the maids seized Talisman and attacked her hair with a pair of scissors. She tore herself free and stamped with rage at the sight of her hair on the floor, but it made no difference.

And the cook and one of the maids seized Talisman and attacked her hair with a pair of scissors. She tore herself free and stamped with rage at the sight of her hair on the floor, but it made no difference.

“There!” the cook said, with vicious satisfaction. “A convict cut. Quite appropriate, really, wouldn’t you say, Talisman Mallerby?”

“There!” the cook said, with vicious satisfaction. “A convict cut. Quite appropriate, really, wouldn’t you say, Talisman Mallerby?”And I waited for Talisman’s familiar upsurge of rage at an insult, but instead I felt only deep fear.

“Because the jury have reached their verdict about what happened in India. And guess what verdict they reached, Talisman Mallerby?”