“You can’t possibly have a message from my brother for me.” Her brother was dead! Was this some kind of imposter, hoping to trick some money from her.

“You can’t possibly have a message from my brother for me.” Her brother was dead! Was this some kind of imposter, hoping to trick some money from her.

The pedlar smiled at her.

The pedlar smiled at her.“Your brother said you wouldn’t believe me. So he sent a sign for you.”

And the pedlar beat time and began to sing:

“Little Lissa lost her shoe.

What a silly thing to do.

She couldn’t find it anywhere.

It was underneath her chair.

Little Lissa lost her shoe.

What a silly thing to do.

She stood and she scratched her head.

It was underneath her bed.”

Matthew had made that song up when she’d been about four years old. It had been a family joke from then on. Only Matthew would have known it.

Matthew had made that song up when she’d been about four years old. It had been a family joke from then on. Only Matthew would have known it.“He’s alive?” She could hardly believe it.

“Alive and well, and in the Low Countries.”

“Alive and well, and in the Low Countries.”“But how did he get there? And – are my parents still alive too?”

The pedlar’s face told her the answer to that one before he shook his head.

“When they were pushed overboard…”

“Pushed overboard? I was told the ship went down!” Her uncle had lied to her. And worse, from the sound of it.

“…your brother was lucky. He was picked up by some fishermen who took him home with them. He didn’t dare try to return to England straight away, but now he is a man full-grown, and will challenge his uncle. But he needs money – the fishermen he’s living and working with are not rich. I will carry it to him – I am much in his debt, for he helped me when I was being set upon by some would-be thieves.”

“But I have no money.”

“But I have no money.”“Your brother said that the rents would be yours.”

Lissa laughed bitterly. “Such as they are.”

She remembered – four years ago now – when her uncle had brought the first rents to her, for her to count.

She remembered – four years ago now – when her uncle had brought the first rents to her, for her to count.

“They only amount to some fifty shillings a year. And my uncle says I cost that much – and more - to feed.”

“They only amount to some fifty shillings a year. And my uncle says I cost that much – and more - to feed.”

Fifty shillings a year! That was ridiculous! My total disbelief exploded inside Lissa, just as the pedlar said much the same.

Fifty shillings a year! That was ridiculous! My total disbelief exploded inside Lissa, just as the pedlar said much the same.“Truly, Madam, I can earn that in a month’s trading. Your uncle has lied to you.”

And anyway, I thought, her uncle had no authority to collect the rents. That was for “the eldest daughter and all the heires male”. I suddenly remembered what the Professor had been telling me.

And anyway, I thought, her uncle had no authority to collect the rents. That was for “the eldest daughter and all the heires male”. I suddenly remembered what the Professor had been telling me.“Is there no man at law whom you could consult, or does your uncle own all the justice here?”

Lissa didn’t think that he did. Her uncle was seldom here – he had just left her here with – she saw it now – Ruth and Beatrice as her jailors. He’d dismissed all the other servants, saying they could no longer afford to keep them. Lissa had hoped that they would find new jobs.

With the news that Matthew lived, and my indignation boiling within her, she was suddenly capable of action.

“I will go and visit Mr Perry. Now. Before my cousins return and lock me up again.”

“I think you had best wash first, else you’ll be turned from his door as a beggar. And here – I’ll give you a comb from my pack, and a ribbon for your hair.”

It was four years since Lissa had been into the village. And what she noticed was that it was looking shabbier than she remembered.

It was four years since Lissa had been into the village. And what she noticed was that it was looking shabbier than she remembered.

The cottages she passed were all looking run-down and as though no-one was taking proper care of them.

The cottages she passed were all looking run-down and as though no-one was taking proper care of them.

As she got nearer Mr Perry’s office, Lissa began to worry. What if he refused to see her? She looked like a beggar girl – she knew she did. What if…? You have to do this, I told her. It’s your one chance.

As she got nearer Mr Perry’s office, Lissa began to worry. What if he refused to see her? She looked like a beggar girl – she knew she did. What if…? You have to do this, I told her. It’s your one chance.By the time she reached the door though, she was shaking with nerves.

She knocked at the door and a manservant answered it.

She knocked at the door and a manservant answered it.“Be off with you – we don’t want beggars here!

“But I want to see…”

“But I want to see…”“Away, I said. Mr Perry has better ways to spend his time that chattering with beggars.”

Lissa was beginning to be desperate. And to make matters worse, she could hear a carriage drawn by a pair of horses approaching in the distance. Beatrice and Ruth coming home! This was her last chance! If they found her here…Her blood ran cold at the thought.

“I am…” She had been about to say Lissa, but decided to use her full name.

“I am…” She had been about to say Lissa, but decided to use her full name.“I am Talisman Malherbe of Ship House, and I wish to see Mr Perry on a matter of urgent business.”

Had Ship had something to do with what happened next? I couldn’t see how, but just as Lissa was being sent away from the lawyer’s house by his manservant, the door was flung open and a plump woman came bustling out, smiling and crying at the same time.

Had Ship had something to do with what happened next? I couldn’t see how, but just as Lissa was being sent away from the lawyer’s house by his manservant, the door was flung open and a plump woman came bustling out, smiling and crying at the same time.

“Lissa Malherbe! My little Lissa! When I heard your voice, clear as day – for shame on you, Tom Miller, turning a Malherbe from your front door. Come you in, my dear, and sit you down by the fire.”

“Lissa Malherbe! My little Lissa! When I heard your voice, clear as day – for shame on you, Tom Miller, turning a Malherbe from your front door. Come you in, my dear, and sit you down by the fire.”It was Lissa’s old housekeeper, Mrs Frumenty. So this was where she worked now!

“There, Mistress Lissa. You look half-frozen, and why have you no shoes? And why have we seen neither hide nor hair of you these past four years? Three times I went up to see you, and was turned away. Sit you there and warm yourself. I’ll fetch the master for you, and find you something to eat and drink too.”

“There, Mistress Lissa. You look half-frozen, and why have you no shoes? And why have we seen neither hide nor hair of you these past four years? Three times I went up to see you, and was turned away. Sit you there and warm yourself. I’ll fetch the master for you, and find you something to eat and drink too.”And Lissa sat down in front of the fire and felt safe for the first time in months and months. The carriage from Ship House rattled past the window, but it didn’t matter now. She was safe here.

A few moments later, Mr Perry came and seated himself beside her.

A few moments later, Mr Perry came and seated himself beside her.“Now, Mistress Malherbe. My housekeeper tells me that you have come asking for my help, and that I must be sure to give it to you, for a sweeter little maid never existed.” His imitation of Mrs Frumenty was wickedly exact, and Lissa smiled, her nervousness vanishing.

“What exactly is the problem?”

“What exactly is the problem?”And Lissa told him: that she had reason to believe that her uncle was stealing the income from her rents. She stayed off her parents’ accident – she had no proof – and the way the cousins were treating her could come next.

“But Mistress Malherbe, as the nearest male relative, your uncle would be responsible for collecting the rents. You could not do so, as a young female.”

“But Mistress Malherbe, as the nearest male relative, your uncle would be responsible for collecting the rents. You could not do so, as a young female.”Lissa raised her head proudly.

“In 1587 – the date is on the rolls – it was specified that the rents may be collected by “the eldest daughter or any heires male.” I am that eldest daughter – and since my parents and brother are gone, I am the only one entitled to do so.”

“Is that so?” A keen look came into his eyes. “In that case, I think we can definitely proceed with the assumption that you have been wronged. Now, is there anything else?”

“Is that so?” A keen look came into his eyes. “In that case, I think we can definitely proceed with the assumption that you have been wronged. Now, is there anything else?”“Yes. My uncle and my cousins have been well-nigh keeping me prisoner to prevent me ever telling of the wrongs being done to me.” And Lissa told him the history of her last four years. His face darkened as he heard it, for he was evidently a kindly enough man. And when Mrs Frumenty came in with food and drink part way through, she burst into tears and hugged Lissa to herself.

“We need proof of these things. The law likes proof. The Malherbe documents – I can examine those tomorrow. Your cousins’ ill-treatment of you: I think I know how to get the proof of that. With your help, I think we can deal with them this very night. This is the year of grace 1664 – to believe that such wickedness can go on is hard indeed! It belongs to the dark ages!” And he told Lissa how he planned to get proof. “But for tonight, you must go back to Ship House again.”

Lissa had tangled her hair and dirtied her face again. Ruth and Beatrice ran her to earth in the kitchen.

Lissa had tangled her hair and dirtied her face again. Ruth and Beatrice ran her to earth in the kitchen.“And where were you, when we came home?”

“I went outside. Into my own garden.”

Ruth hit out at her, and Lissa’s face told her fear.

“Your garden? I do not think so. Paupers do not own gardens. This is our house now, and we may do as we please – with it and with you.”

“And then Beatrice started in on Lissa as well.

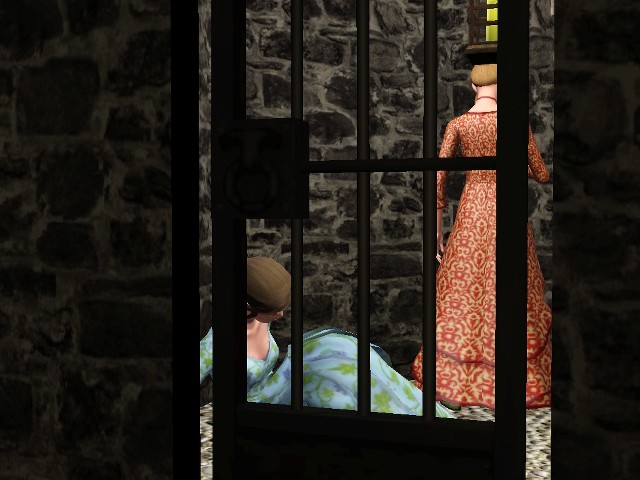

“And then Beatrice started in on Lissa as well.“I think we’ll put a final stop to the freedom you seem to take for yourself. Ruth – methinks we have some chain in the dungeon. And there is a ring on yonder wall by the fireplace. We’ll chain her by the ankle, and then she’ll wander no more.”

Lissa flinched away from them as they approached her. But they carried out their threat: dragged her downstairs and attached a chain to her ankle, the dragged her up again and fastened the chain to the kitchen wall near the fireplace.

“And that will keep you where you belong!”

And that was when Mr Perry and Tom Miller came into the room.

And that was when Mr Perry and Tom Miller came into the room.“I think that is all the proof that is needed. All that you said has been heard by two witnesses. All that you did is clearly visible. Tom, these two can go in the dungeon for the night – and tomorrow, they go before the magistrate.”

And when Tom had marched them downstairs, one after the other, he came over and released Lissa.

“Tom will stay here to guard them, Mistress Malherbe, and you can come and spend the night at my house. I know Mrs Frumenty is putting a hot brick in the bed for you even now.”

“Tom will stay here to guard them, Mistress Malherbe, and you can come and spend the night at my house. I know Mrs Frumenty is putting a hot brick in the bed for you even now.”“I thank you kindly, Mr Perry. I would like to go and find some better clothes to take with me, if I may.”

And she also used the time to sneak downstairs and look at Beatrice and Ruth locked in the very dungeon they had thrown her into.

And she also used the time to sneak downstairs and look at Beatrice and Ruth locked in the very dungeon they had thrown her into.

Then she went upstairs, to find some clothes. She would take from her cousins – they had stolen enough from her. But I wanted her to look for something else too. There was only one room I’d never been into, and it was her parents’ old room. As soon as she walked in, I knew the guerdon was in here. I could almost feel it, making the air pulse. And the only place it could be was under the bed. I forced Lissa to reach out for it – and as soon as she held it, the darkness folded in around me.

Then she went upstairs, to find some clothes. She would take from her cousins – they had stolen enough from her. But I wanted her to look for something else too. There was only one room I’d never been into, and it was her parents’ old room. As soon as she walked in, I knew the guerdon was in here. I could almost feel it, making the air pulse. And the only place it could be was under the bed. I forced Lissa to reach out for it – and as soon as she held it, the darkness folded in around me.

No comments:

Post a Comment