Ariadne was taking a week off work and, as usual, she’d gone straight to the community gardens. Being outside, and out of the office was wonderful! Getting soaked to the skin in a sudden summer rain-shower wasn’t on her list of Fun Things To Do In My Holidays though, so she took shelter in the gazebo, and just enjoyed looking at something other than the four beige walls of the office, and reflected on the fact that her last holiday had been five months ago.

Ariadne was taking a week off work and, as usual, she’d gone straight to the community gardens. Being outside, and out of the office was wonderful! Getting soaked to the skin in a sudden summer rain-shower wasn’t on her list of Fun Things To Do In My Holidays though, so she took shelter in the gazebo, and just enjoyed looking at something other than the four beige walls of the office, and reflected on the fact that her last holiday had been five months ago.Five months ago, an investigative journalist called Pete Wainwright had kept an appointment he’d made with Dr Wolvercote.

Quiet, a little shy, a little reserved: Ariadne’s colleagues thought she was a bit dull and nondescript, and certainly the way she dressed and behaved suggested that. But all Ariadne wanted was security and safety. Her parents had died when she was fourteen leaving nothing but debts and a remarkable shortage of relatives. One distant cousin had been traced, but the link was so tenuous that no-one was surprised when he didn’t respond.

Quiet, a little shy, a little reserved: Ariadne’s colleagues thought she was a bit dull and nondescript, and certainly the way she dressed and behaved suggested that. But all Ariadne wanted was security and safety. Her parents had died when she was fourteen leaving nothing but debts and a remarkable shortage of relatives. One distant cousin had been traced, but the link was so tenuous that no-one was surprised when he didn’t respond.Four years of being shifted from place to place while she finished school had followed, and then four years of poorly-paid jobs and crummy rented rooms in shared houses. But finally she had a safe – if boring – job, and a little house of her own. Rented, true, but she didn’t have to share it with anyone. She’d learnt to drive as well, and now had a little car. And if sometimes a voice in her head suggested that there might be more yet, and did she really want to spend the next forty years in an office, she ignored it. She’d achieved safety, and she wasn’t going to stretch after anything more.

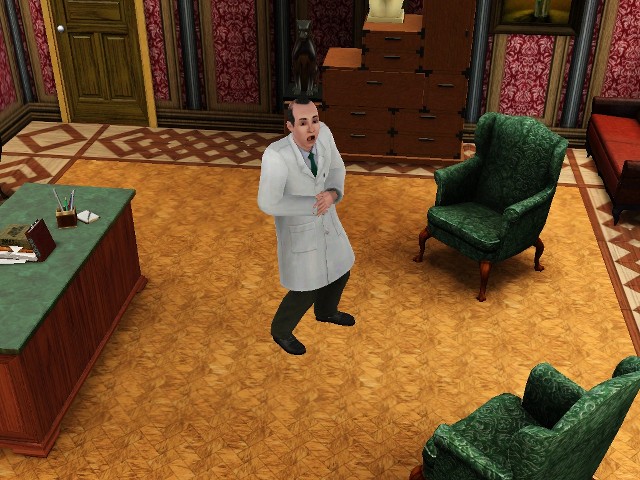

A hundred and fifty miles away from Ariadne sitting in the pavilion and listening to the rain on the roof, a man called Dr Wolvercote sat at his desk and winced at the indigestion pains that were shooting through him again. Maybe he ought to take the time to go and see a GP.

A hundred and fifty miles away from Ariadne sitting in the pavilion and listening to the rain on the roof, a man called Dr Wolvercote sat at his desk and winced at the indigestion pains that were shooting through him again. Maybe he ought to take the time to go and see a GP.

He got up from his desk, to see if standing up would help, and a sudden pang, worse than all the rest, shot through him.

He got up from his desk, to see if standing up would help, and a sudden pang, worse than all the rest, shot through him.

He collapsed, groaning in agony.

He collapsed, groaning in agony.

Half an hour later, one of the staff found him lying there dead on the floor.

Half an hour later, one of the staff found him lying there dead on the floor.

Ariadne spent a happy day in the garden, once it had stopped raining. She walked home, happily planning her next day – a trip to the garden centre to buy seeds for her own tiny garden, and then the afternoon in the community garden again. And the day after tomorrow, the usual trio of old men would be there, and they’d give her lots of conflicting advice about how she should be doing things, and argue amicably among themselves, and she’d have company. She’d made herself a late supper, and was just beginning it, when a motorcycle pulled up outside.

Ariadne spent a happy day in the garden, once it had stopped raining. She walked home, happily planning her next day – a trip to the garden centre to buy seeds for her own tiny garden, and then the afternoon in the community garden again. And the day after tomorrow, the usual trio of old men would be there, and they’d give her lots of conflicting advice about how she should be doing things, and argue amicably among themselves, and she’d have company. She’d made herself a late supper, and was just beginning it, when a motorcycle pulled up outside.“Package for Ariadne Keswick-East. Sign here.”

And then he was gone – just an anonymous dark shape in the night, on his way to another delivery. She went back into the house to open the package, and got the shock of her life.

The letter marked Read This First was quite long and detailed.

And then he was gone – just an anonymous dark shape in the night, on his way to another delivery. She went back into the house to open the package, and got the shock of her life.

The letter marked Read This First was quite long and detailed.“…so, when I was informed of your existence, I was pleased to hear that I had someone to hand things on to. Had you been a boy, I would naturally have adopted you, and had you educated to follow in my footsteps. Girls, however, do not normally have the necessary aptitude for the serious scientific research I have been pursuing. I am aware that times have changed slightly, so I have followed your school career, but I have not been inclined to change my mind, or to regret not having adopted you.

However, when this letter reaches you, it will be because I have died. You are a relative, and it has long been obvious to me that in some matters, only family can be trusted. On receipt of this, you need to present yourself immediately at the office of Messrs Portaway, Hollinshed and Arbuckle. They will be expecting you, and will be ready to meet with you no matter what day it is. There are certain extremely urgent matters that must be dealt with immediately. I should perhaps point out that I am making you my heiress, so there will be no financial loss to you should you have to leave you job to attend to these affairs. You will in fact be very comfortably circumstanced for the rest of your life, whether you take a job or not…”

It took Ariadne a long time to take in all the implications, but one thing was clear; she was going to have to see these solicitors. She phoned the office number, to leave a message on their answering machine, but was surprised when the phone was answered instantly, by a very polite young gentleman, who was hoping that she would have called, and had in fact been told to be there on duty all night solely to answer her call.

It took Ariadne a long time to take in all the implications, but one thing was clear; she was going to have to see these solicitors. She phoned the office number, to leave a message on their answering machine, but was surprised when the phone was answered instantly, by a very polite young gentleman, who was hoping that she would have called, and had in fact been told to be there on duty all night solely to answer her call.“Dr Wolvercote was a very important client. We take his instructions very seriously. Can you be here at 9 am tomorrow morning? – we can send a car to collect you.”

A little dazed, Ariadne agreed, and then went back to her half-eaten supper. It looked as though she was being offered the security she’d always craved. She didn’t think she’d missed out on much by not being adopted by Dr Wolvercote – he sounded a bit humourless. She’d better put on her smartest clothes tomorrow, though – she didn’t think her gardening dungarees would quite do. And she was still going to get those seeds bought! Tomorrow morning might well be booked up, but she could still get in the garden in the afternoon.

The solicitors’ offices were impressively big – and the car they had sent for her had been impressively expensive. Ariadne began to feel somewhat under-dressed, despite these being her smartest clothes.

The solicitors’ offices were impressively big – and the car they had sent for her had been impressively expensive. Ariadne began to feel somewhat under-dressed, despite these being her smartest clothes.

But the smart young man who showed her into the waiting room, and asked her if she’d like a cup of coffee couldn’t have been politer. He apologised for the fact that they might have to keep her waiting for five minutes or so, showed her a seat, the pile of books on the table, and then left when she refused the coffee.

But the smart young man who showed her into the waiting room, and asked her if she’d like a cup of coffee couldn’t have been politer. He apologised for the fact that they might have to keep her waiting for five minutes or so, showed her a seat, the pile of books on the table, and then left when she refused the coffee.

Ariadne picked up one of the coffee table books – a beautifully illustrated volume on modern French gardens – but had hardly begun to look at it when the other door opened, and Mr Hollinshed ushered her into his office.

Ariadne picked up one of the coffee table books – a beautifully illustrated volume on modern French gardens – but had hardly begun to look at it when the other door opened, and Mr Hollinshed ushered her into his office.

Any hopes Ariadne had of getting into the garden that day slowly faded as the morning went on. There was an endless amount of form-filling, presentation of the proofs of identity they’d asked her to bring, more form-filling – all punctuated by excellent coffee, little cakes and then a selection of delicious sandwiches. Mr Hollinshed apologised for not being able to take her out for lunch, but explained that Dr Wolvercote had wanted the formal business transacted within one working day.

Any hopes Ariadne had of getting into the garden that day slowly faded as the morning went on. There was an endless amount of form-filling, presentation of the proofs of identity they’d asked her to bring, more form-filling – all punctuated by excellent coffee, little cakes and then a selection of delicious sandwiches. Mr Hollinshed apologised for not being able to take her out for lunch, but explained that Dr Wolvercote had wanted the formal business transacted within one working day.

Then, in the afternoon, the smart young man talked her through setting up a web-based bank account, and then transferred a sum of money into it that made her feel quite giddy.

Then, in the afternoon, the smart young man talked her through setting up a web-based bank account, and then transferred a sum of money into it that made her feel quite giddy.“This is by no means the whole of his wealth, but some of that is bound up in his property. As from now, you have authority to do anything you like to the property and its contents, although should you choose to sell the property, we will not be able to close the sale until probate has been completed.”

When she was asked about her job, and admitted that she did not find it in the least inspiring, nor was she happy there, it was suggested she hand in her resignation straight away.

“The firm will take care of any salary that might either be owed, or be deductible.”

It was actually quite fun to telephone the office and hand in her resignation!

“Dr Wolvercote did not wish you leave a job you considered to be your vocation, but even then, he hoped that you would be able to take a month’s leave. He had a task he felt only you could fulfil.”

When she looked a question at him, he said that they had sealed instructions to hand over to her when all other formalities had been completed.

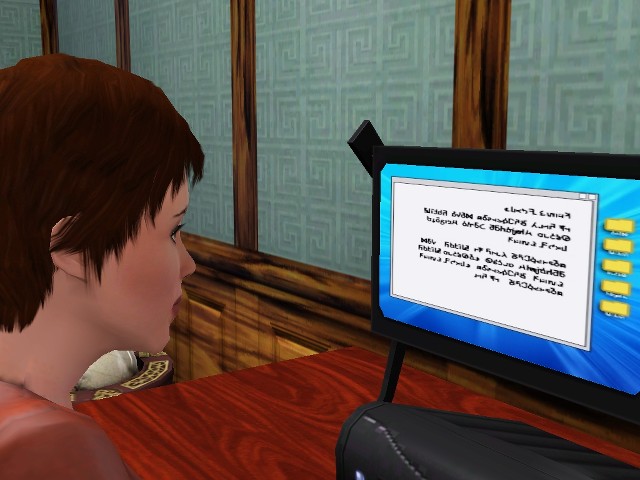

Finally, they left her alone in the office to read one last file. The password to access the file was in a sealed envelope: when she typed it in, the words appeared before her eyes.

Finally, they left her alone in the office to read one last file. The password to access the file was in a sealed envelope: when she typed it in, the words appeared before her eyes.“…and so, I need you to go, immediately, to Wolvercote House, and deal with what you will find in the attics. The objects up there will need some maintenance, but that will not be beyond your capabilities or intelligence. What you do with these things is entirely up to you, but from what I have heard, Mr L. might well be willing to take them off your hands. If he offers less than six million, turn him down. One of them alone is worth twice that. Insist that he takes them all, or none. This is his personal number, and the code word you will need is Endeavour. Now, as to entry instructions…”

By the end of the file, Ariadne was thoroughly confused. At that price, they must be antiques – and possibly stolen, or otherwise dodgy, hence all the secrecy. In which case, the sooner she was shot of them, the better. The file ended:

By the end of the file, Ariadne was thoroughly confused. At that price, they must be antiques – and possibly stolen, or otherwise dodgy, hence all the secrecy. In which case, the sooner she was shot of them, the better. The file ended:“The entry instructions will be given to you, along with the keycard you will need. Once you are sure you have understood this file, type in DELETE and press return, and it will be deleted. I have entrusted you with my wealth: do not fail me in this urgent task.”

She re-read it, twice, to make sure she’d understood it, and then typed DELETE.

Dr Wolvercote had left very precise instructions about what was to happen in the event of his sudden death, not only with his solicitors, but also with his staff. Within two hours of his death, a fleet of private ambulances was at Wolvercote House, transporting the clients back to their homes, or to another institution. The staff systematically deleted all confidential records from the computers and re-formatted the hard drives. The equipment in the treatment rooms was dismantled, and a specialist recycling firm came to take it away. By midnight, all the patient rooms had been emptied: only the fixtures and fittings remained. Anyone walking in through the front door would find only an empty shell of a clinic. The rehabilitation flat was left alone though, and the freezer re-stocked.

Dr Wolvercote had left very precise instructions about what was to happen in the event of his sudden death, not only with his solicitors, but also with his staff. Within two hours of his death, a fleet of private ambulances was at Wolvercote House, transporting the clients back to their homes, or to another institution. The staff systematically deleted all confidential records from the computers and re-formatted the hard drives. The equipment in the treatment rooms was dismantled, and a specialist recycling firm came to take it away. By midnight, all the patient rooms had been emptied: only the fixtures and fittings remained. Anyone walking in through the front door would find only an empty shell of a clinic. The rehabilitation flat was left alone though, and the freezer re-stocked.Finally, all the sophisticated electronic locks were set to prevent anyone entering the clinic – or leaving it, but that wasn’t such an issue- and the last member of staff walked out, triggering the locking system behind him as he went.

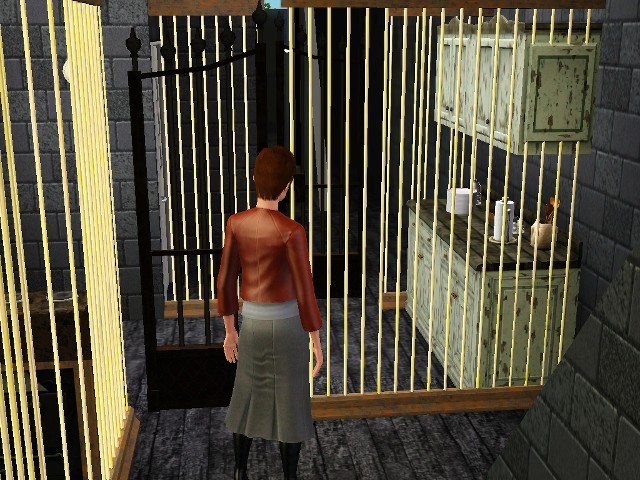

Ariadne parked her little car at the back of the forbidding grey building, as she’d been told. She’d brought an overnight bag – apparently, there was a flat she could use, contained inside the building, and the freezer had been left stocked for her. This wasn’t where she’d have chosen to stay, but it had been a long drive, and the place was very remote.

The key card let her in through the back door.

“Once you remove the card from the reader slot, the door will automatically re-lock. Do not lose the card. There is no mobile phone signal at Wolvercote House, and although the heating, lighting and water are all functioning, the telephone line has been disabled.”

She crossed the tiled hall, and went into the library.

She crossed the tiled hall, and went into the library.

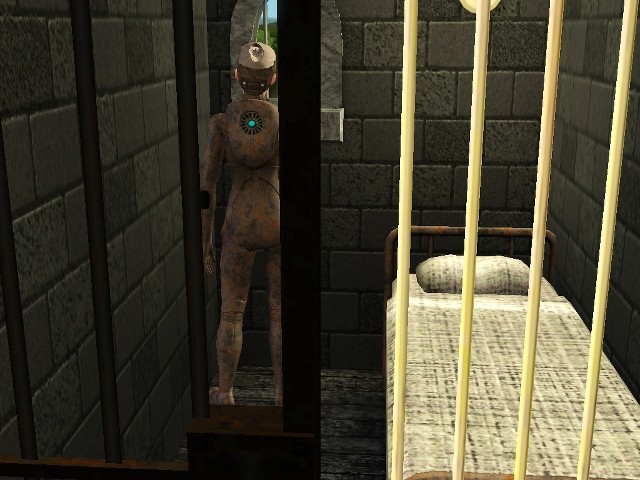

Pete was beginning to think that something was wrong.

Pete was beginning to think that something was wrong.Once a day, Dr Wolvercote came up and fed them, and took away the full chamber pots from under their beds. But he hadn’t been up for three days now. And he’d been talking about some new equipment he’d just had installed, and some modifications he’d made to the machine: he’d been planning to experiment on Pete some more, and also on Elise. It wasn’t like him to pass up on that sort of opportunity.

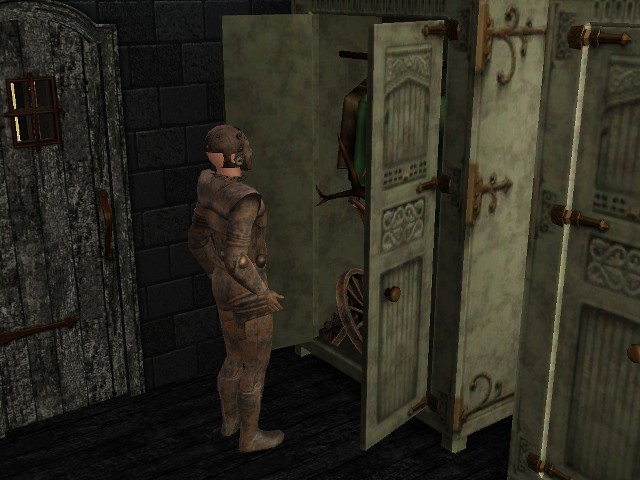

Thankfully, Pete had been able to get out of his cell – at least he’d been able to give the others some water, and a little food. There was enough in the kitchen cupboards to last at least a year, Pete reckoned – mostly dried stuff that could be reconstituted with boiling water. But he hadn’t dared cook anything, or take too much in case Dr Wolvercote realised that one of them could get out of their cell.

He’d gone along the corridor, past the others as they were sleeping, and into the old laboratory. He’d looked in the cupboards there and found some very old clothes, and a number of objects that looked like they had decidedly sinister uses, most of which he could guess with ease. But was there anything here that he could use to overpower Dr Wolvercote? He wasn’t sure. The doctor always came up armed with a Taser – and he was stuck inside a metal suit.

He’d gone along the corridor, past the others as they were sleeping, and into the old laboratory. He’d looked in the cupboards there and found some very old clothes, and a number of objects that looked like they had decidedly sinister uses, most of which he could guess with ease. But was there anything here that he could use to overpower Dr Wolvercote? He wasn’t sure. The doctor always came up armed with a Taser – and he was stuck inside a metal suit.

Pete was just debating whether to go and get another drink for everyone – and getting seriously annoyed by the smell coming from under his bed, but he didn’t dare empty the chamber pot – when he thought he heard a noise from downstairs.

Pete was just debating whether to go and get another drink for everyone – and getting seriously annoyed by the smell coming from under his bed, but he didn’t dare empty the chamber pot – when he thought he heard a noise from downstairs.

Just as it said in the letter, a section of bookcase swung open under her hand. She picked up her bag, took out the card, and went through and headed up the stairs behind the door. It swung shut behind her.

Just as it said in the letter, a section of bookcase swung open under her hand. She picked up her bag, took out the card, and went through and headed up the stairs behind the door. It swung shut behind her.

As she climbed the stairs, she began to feel more and more apprehensive. She clung on to the handles of her bag as if it was her link with reality and safety.

As she climbed the stairs, she began to feel more and more apprehensive. She clung on to the handles of her bag as if it was her link with reality and safety.

There were bolts and bars everywhere. But the letter had said she would be quite safe.

There were bolts and bars everywhere. But the letter had said she would be quite safe.“Your key will open the next two locks simultaneously. Leave it in the reader slot, and then there is no danger of the door locking behind you.” She dumped her bag at the top of the stairs.

Pete had been looking out of the window when he heard the footsteps on the stairs. One set only – but they weren’t Dr Wolvercote’s.

Pete had been looking out of the window when he heard the footsteps on the stairs. One set only – but they weren’t Dr Wolvercote’s.

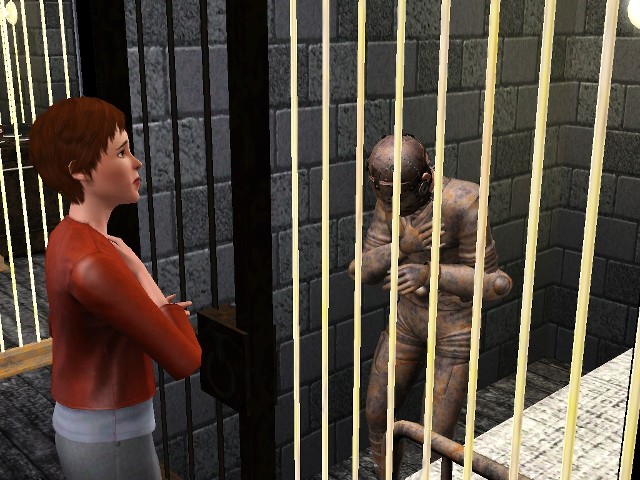

And then there was a strange woman standing in front of his cell door, looking like she couldn’t believe what she was seeing. Sheer worry for her drove Pete to speech.

And then there was a strange woman standing in front of his cell door, looking like she couldn’t believe what she was seeing. Sheer worry for her drove Pete to speech.“You need to get away! Now! Quickly! If Dr Wolvercote finds you here, you’ll end up like this – or worse. Go! Now! Hurry, please!”

He looked like a robot. But he sounded human. Now Ariadne was beginning to understand why there had been such an insistence on secrecy in Dr Wolvercote’s instructions. But he had suggested selling what she found in the attics!

He looked like a robot. But he sounded human. Now Ariadne was beginning to understand why there had been such an insistence on secrecy in Dr Wolvercote’s instructions. But he had suggested selling what she found in the attics!Her heart was bumping painfully against her ribs – but the robot man wasn’t actually threatening her. And there was a locked door between them.

She made herself turn to face him.

“Dr Wolvercote’s dead.” She couldn’t say “I’ve come to deal with you.” Instead, she said, “I guess I’ve come to rescue you.”

He paused as though he couldn’t quite take the news in.

“I’ll go and get help, shall I? Find some firemen at least, to cut through these bars. I’ll have to go down the road a way though – I’ve got no signal here.”

Pete’s mind was racing. He seemed to see possibility after possibility – and nearly all of them ended badly. He needed more time, and more information.

Pete’s mind was racing. He seemed to see possibility after possibility – and nearly all of them ended badly. He needed more time, and more information.“Wait. Don’t go away just yet. Could you get me a drink of water? No-one’s been near us for three days. He watched her closely, saw the look of horror and pity cross her face.

“Thank you,” he said, when he’d drunk the water. He kept his head low and his shoulders slumped, trying to look as harmless as possible.

“Thank you,” he said, when he’d drunk the water. He kept his head low and his shoulders slumped, trying to look as harmless as possible.“Could you do the same for the others? But with the one at the far end – Olaf – he can’t see. You’ll have to put it into his hand for him. Just put it on the floor for the others – they’re shy of strangers. And then – will you come back and talk to me some more? I’ve had no company for five months now.”

She did as he asked. All four of them were unsettling to see, but one of them looked positively dangerous.

She did as he asked. All four of them were unsettling to see, but one of them looked positively dangerous.

Pete came as close to the bars as he could, to talk to her. He wasn’t going to tell her that he could open the door – he must look pretty scary, judging by her face when she first saw him. She’d probably feel a lot safer if she thought he was locked away from her.

Pete came as close to the bars as he could, to talk to her. He wasn’t going to tell her that he could open the door – he must look pretty scary, judging by her face when she first saw him. She’d probably feel a lot safer if she thought he was locked away from her.“You say Dr Wolvercote’s dead. So who’s downstairs?”

“No-one. The place is deserted.”

“So how come you’re here?” Then he paused. “I’m sorry – I’m forgetting my manners. I’m Pete Wanwright. I was an investigative journalist – freelance, and roving. I came here to follow up a story about the asylum’s past – strange practices in Victorian times – and found out that they were still going on, and happening to me. What’s your name?”

Ariadne relaxed a little more. He might look like a metal monster, but he sounded very normal. Poor man – locked away for five months.

Ariadne relaxed a little more. He might look like a metal monster, but he sounded very normal. Poor man – locked away for five months.“I’m Ariadne Keswick-East – and I was an office worker until yesterday. Very boring – nothing like your job.”

“Probably a lot safer!”

“Oh, safe – that’s all I’ve ever wanted to be.”

Pete was a very good journalist. She found herself telling him her life history, and by the end of the story, he no longer seemed like a metal monster, but another kind human being.

“But why you?” Pete asked. What was this nice shy girl doing here? “How come you’re the one to rescue us?”

“But why you?” Pete asked. What was this nice shy girl doing here? “How come you’re the one to rescue us?”“It’s a long story,” she said tentatively.

“I’ve got five months of silence saved up! Talk!”

So she told him the whole story of the previous day – every detail, apart from the actual staggering amount of money that was now in her bank account. Right down to how the electronic key card had let her in, and she’d seen him standing there.

“But now we can get you all out.”

And then what? Pete thought. Someone would probably get him out of this suit, but what of the other four? They’d end up in institutions somewhere else. But he was sure that the key to restoring them was here, in Dr Wolvercote’s laboratories, and in his records. He suddenly realised he didn’t want to leave yet – and he didn’t have to.

“So you’re his only living relative? And his heiress? And you can do whatever you like with his property?”

“So you’re his only living relative? And his heiress? And you can do whatever you like with his property?”Ariadne thought he was asking her for reassurance that she really did have the power to get them all out.

“Yes. I can do anything I want here. I have the authority, the solicitor said. Except if I sold it tomorrow, it’d take a while for the sale to actually go through.”

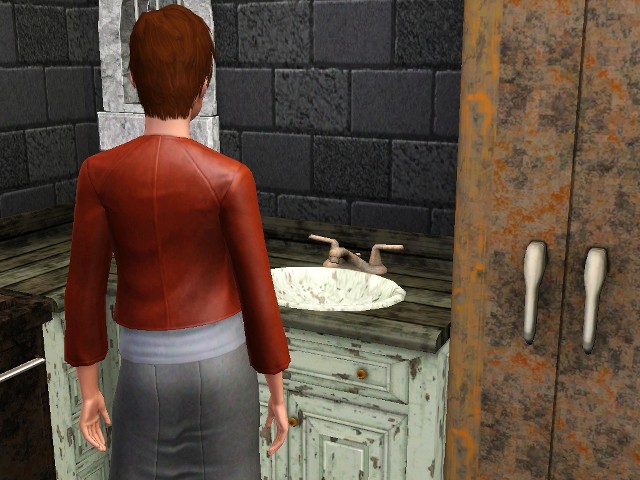

Cold and calculating, Pete’s brain began to formulate a new scenario. One that might lead to a happier ending for at least some of them. He drooped, artistically.

“Could you fetch me some more water, please? I haven’t talked for so long in ages, and my throat hurts.”

Ariadne went gladly to the sink. She didn’t hear his footsteps behind her, but something hit her on the head, and her world dissolved into darkness.

Ariadne went gladly to the sink. She didn’t hear his footsteps behind her, but something hit her on the head, and her world dissolved into darkness.

When she came to, she was lying on the old settee that had been at the head of the stairs. But things felt strange.

When she came to, she was lying on the old settee that had been at the head of the stairs. But things felt strange.

No comments:

Post a Comment